Brussels

Airlines dropped me in the middle of the rain.

Airport

control was chaotic as could be expected but I succeeded to find a successful

track to my luggage. My suitcase had already been taken from the belt, but theft

was prevented by checking the tag at the exit.

My

daughter had told me the story of two doctors who took a common taxi at an African

airport and they never showed up again.

Being

welcomed by my name on a sign hold up by a driver and accompanying car, felt as

a first guarantee for safety within a country that had suffered civil war and Ebola

for decades.

As many West African countries, Liberia had been a transit point in slavery transport.

In the beginning of the 19th century, relieved black American slaves came back to Liberia to establish firstly an American country and then an independent state oriented to American structures and values.

In the beginning of the 19th century, relieved black American slaves came back to Liberia to establish firstly an American country and then an independent state oriented to American structures and values.

During the last two centuries, Liberia

has always been exploited and abused by other countries through poorly

negotiated contracts

because of their mining products (rubber and others).

It was only in the sixties that native Liberians

obtained the right to vote and in the nineties and in the beginning of the 3rd

millennium a

terrifying civil war occurred over the country.

One of the former presidents

Samuel Doe was

killed by Prince Johnson in a cruel way and the government of Charles Taylor, lasting until 2006, was nothing less than an

authoritarian military state.

It took until the presidency

of Mrs. Ellen Johnson,

as the first female president in Africa, in 2006, that a peaceful transition to democracy occurred.

She came from the World Bank and established at

least on the

political side

a more stable

government but

economic development

was almost

completely destroyed

by the Ebola crisis in 2014.

Recently her party lost the elections

and since one year a famous formal

football player,

George Weah, has taken the highest position in the country.

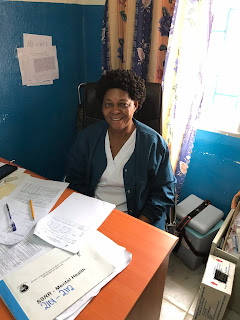

I was welcomed by Florence

-I thought Nightingale- but she died a long time ago, or Griffith- but her

nails where short cut- and it took me a few rehearsals to remember that her

last name was Yahnquee Kiatamba.

Beside Zoe Doe, she was

part of the NCD team headed by Dr Fred Amegashie, a distinct cell within the

Ministery of Health responsible for the management of Non Communicable Disease

as diabetes, hypertension, COPD and cancer.

At the occasion of the

Health Policy program in the Tropical Institute of Antwerp, I met Vera Mussah, head

of the PBF unit of the Liberian Ministery, and she created the opportunity for

a mission of our team focused on cancer policy in Liberia.During the following interviews, I would learn that the last name revealed whether people were from an Afro-American background (10%) or a native Liberian background (90%).

At this moment -writing

the story- the guardian who had started to shout to all the drivers who tried

to find a spot at the hotel parking, came to me a little hesitating to request

whether I could move a little bit to the left.

I presumed he had

waited for more than half an hour to dare chasing me away and I rewarded his

courage by moving friendly to the place he designed me.

Anyway, short pants and

a white skin still makes the difference.

Florence guided me to the

suburbs of the ministerial kingdom with the request whether I could have a

short talk with Mrs. Jallah,

She didn’t seem to have

the right position or credentials to pass the bureaucracy and while going back

to her office she suddenly was called back that the minister was available to

see us.

All the barriers fell down

until we arrived at the door of the minister’s office :" strictly forbidden to

take electronic devices within the office.”

A few urgent matters preceded

us in the waiting queue until we were welcomed by Mrs.

At the end of my 2-days

interview itinerary, I would never had postulated that the ambition of the project

was to establish Liberia as an example for cancer policy and her slightly

cynical look at the occasion of my remark, taught me that my cheap buy-in wasn’t

really appreciated.

As I would learn in the

following interviews, my introduction about my professional background was

politely accepted but not more than a step over to the presentation of my dialogue

partner’s history, beliefs, ideas and intentions.

The minister wanted to

establish five or six ambulatory cancer centres in the country for prevention,

counselling, screening, early diagnosis and chemotherapy treatment. She was in

favour of independent small cancer centres as a kernel of expertise from where

people could be referred to hospitals if necessary for example in case of

surgery.

She referred me to Dr. Ann

Marie Beddoe, an American gynaecologist who was doing some developing work in

the JFK University Hospital for many years.

Mrs Jallah reassured access

of me to her the same day by giving her an instant call.

The minister-assistant

of prevention, Joyce Sherman, seemed to have no intense connection with the

cancer policy.

She was more specific

about programs on diabetic education and the delivery of HPV-vaccines to 14/16

years old girls.

She had worked for the

WHO, USAID and since twelve years for the Liberian government.

She had a bachelor in

nursing with an attention for public and child health.

She emphasised that the

initiatives concerning cancer were fragmented and the aim was to analyse what

was already there and then connecting the dots.

“There is no lack of

evidence and nice policy documents”, she emphasised : “but it all blocks at the

level of implementation.”

90% of the health

budget of Liberia was spent on the pay of employees and administration. So only

10% was available for service delivery.

We had to realise that

all improvement in infrastructure, education and quality had to be funded by third

parties.

At this moment at JFK,

a 5-million-dollar medical image center with MRI and CT was built with American

money.

Driving from the hotel

to the ministry, I remembered the construction of a huge new building for

government agencies, sponsored by the Chinese and later the Japanese would

welcome us in the JFK building for maternal care: the international competition

for conquering Africa by development aid….

One hour later, again

we had to pass the initial barrier of bureaucracy to meet Dr. Kaieh, the

chief medical officer of the Ministry of Health.

Although it seemed to

me that Florence had made appointments with all these responsible people,

nevertheless every time we were welcomed as an unexpected guest.

It seemed that 20

minutes of humble waiting was building up a minimum level of confidence to be accepted

for a visit.

Entering

the office of Dr. Kaieh was like entering a world of rewards an certificates of

high standard education with a kind of military flavour due to his tight suit.

He

tolerated a short introduction of myself and then he referred me to a picture

on the wall with a woman and a young boy lying on a bed.

“That’s

why I’m here”, he started his story : “My mother was blind at one eye and I was

mocked for that at school. She had had bacterial conjunctivitis.

Although

we were poor and there was no perspective for university, I promised my mother

I would become a doctor and travel in Liberia from city to city to deliver to

the people convenient care.

When

I had finished high school, I had no opportunity to obtain a master’s degree or

to become a medical doctor as I had dreamed.

So,

I started to do voluntary work in hospitals such as cleaning, until I was

noticed by a surgeon, dr Stevenson, who was surprised I was spying his clinical

work in the operation theatre. He offered me to pay for obtaining a university

degree but unfortunately, he died after two years.

But

I got a scholarship to have a medical education in the United States where I

obtained my medical degree from 1988 to 1995.

In

the meantime, my mother had died during the civil war in 1994.

After

graduation, I came back to Liberia and worked at JFK, and from 1998 to 2001 I

was medical director at the Ganta Hospital.

Within

the political tense and dangerous situation, I got almost killed and I left the

country for the United States in 2001.

I

worked in the Sacred Hospital of Chicago and after a while I completed a master

in health care administration.

From

2004 to the end of 2010, I was the public health director in North Carolina.

I

asked my father to move out from Liberia and to join me in the United States

but he refused.

I

was applying for another job in New York as coincidently I focused on the

picture of me and my mother lying on the bed and I started crying.

I

realised I had not fulfilled my promise.

In

search of a new house in New York, I got a call from the president of Liberia,

Ellen Johnson, who wanted me to give a speech at the inauguration of a hospital

constructed by the Chinese in Tapeta, the 26th July 2010.

It

was a brand-new hospital built next to an old one once constructed by the

Taiwanese but partly destroyed during the war.

At

the occasion of this inauguration, I met the Chinese ambassador and aligned

with president Johnson, they both convinced me to take the lead of this

hospital.

I

could not resist to keep my promise to my mother and to come back to Liberia,

although I lost my wife by this.

Due

to my expertise in prevention of biological war, I became the medical

responsible for Ebola policy and when the epidemic was over, I arrived at this

post of chief medical officer."

He

didn’t seem to appreciate I shortly interrupted his story as his loyalty to his

mother and the fulfilling of his promise had become the mantra of his life

which he wanted to share as a kind of universal mission.

“What

do you want to achieve in the following years, what’s your dream?” I tried to

connect his impressive story to a new challenge for the future

“If

you really want to change something in the system, it all starts with leadership

and management”, he answered : “My dream is to establish a high end health care

management education as a leverage for a better quality of care in Liberia.”

“Maybe

we can be partners.” I aligned to his mission.

Dr.

Cooper was the Assistant Minister for Curative Care.

She

explained that except of the public sector (about 75%) there were a lot of

faith-based hospitals and also private for profit institutes in Liberia.

Concerning

new initiatives, she referred to the medical imaging centre that was built now in

JFK, the plans for radiotherapy, the actual chemotherapy unit in Hope for Women

and the nearby establishment of a state of the art unit for breast cancer and

cervix cancer in JFK in cooperation with dr. Ann Marie Beddoe.

For

specialised training for doctors she referred to the programs of of the

Liberian College of Physicians and Surgeons and she admitted that for most

highly specialised medical education ,doctors had to be send abroad.

Her

lack of Liberian accent and the light brown color of her skin, revealed that

she was an American.

Ann

Marie Bedoe had had a professional career as a gynaecologist, but she had

limited her clinical activity, that means she stopped doing surgery but was

still involved in clinical oncology especially for breast and cervix cancer.

She

had a special interest for global and woman’s health.

She

started to do some voluntary work in the JFK hospital about 10 years ago and

recently she was also involved in a project on building health work force

funded by the World Bank.

Her

support in enhancing quality in breast and cervix cancer was not funded by this

project but by her private donation fund.

She

came to Libera about every 2 months.

During

the last years she took the initiative to train a pharmacist and a nurse in the

Mount Sinai hospital in New York, in order to prepare and administer

chemotherapy. For diagnosis they worked with FNA, or Fine Needle Aspirations.

At

the moment, the unit for gynaecology and maternity had the disposition of an

Ugandan pathologist and a second one in the country was linked to the hospital

in Tapeta while three other pathologists were in training in Ghana.

In

the future they considered tele-consulting for complex case.

Laminar

airflow furniture for more or less safe preparation of anti-cancer drugs was

available.

The

budget for cytostatic drugs was still a problem.

For

screening she had proposed a method of visual inspection with acetic acid

smears. Screening of APV was ongoing but palliative care was an issue. It was

her conviction that first a palliative care unit within the university hospital

should be set up with education of nurses and social workers and from that

point as a leverage for home care.

In

her opinion, conditions were acceptable to start up with the chemotherapy unit

in September.

At

the occasion of a short visit at the chemotherapy unit in the private facility “Hope

for Women”, we met one patient who couldn’t attend the day before and she was

alone because treatment was only 3 days a week.

I

wondered, based on my experience as hospital manager, how they could provide

three nurses for one patient and since the staff was available, why not

treating more patients?

The

chemo was prescribed in the paper medical file of the patients and apparently

nurses mixed the anti-cancer drugs without special precautions.

Dr.

Ann Marie Bedoe tried to hide some little skepticism concerning the quality and

safety of this ambulatory unit.

She

admitted that she had held the pen in the extensive cancer policy letter that

was prepared and approved by the cancer committee.

Initially

focus would be put on breast and cervix cancer.

Having read it thoroughly, it elicited in me a great respect for the clinical knowledge and strategic vision with “smart” goals in setting up this policy, although I felt quite a substantial gap between the medical / public health language and concepts and the extent to with the NCD-committee would be able to materialise the requirements and implement the program.

Having read it thoroughly, it elicited in me a great respect for the clinical knowledge and strategic vision with “smart” goals in setting up this policy, although I felt quite a substantial gap between the medical / public health language and concepts and the extent to with the NCD-committee would be able to materialise the requirements and implement the program.

Next day we were not welcomed by Adolfos Kenta, the community

health department director van Montserrado County.

After

a short talk with one of her deputies, a sudden intense teleconferencing

indicated that the big boss was considering to join us.

“Mr.

Deputy” was banned to the next table and we started our explorative meeting on

NCDs, especially cancer.

I

stucked a while with the administrative reporting system as we were shown that

all relevant administrative and medical information had to be filled in in a

prestructured form by the treating doctor or nurse.

Information

from these individual files was aggregated in a huge book as a kind of super excel

on paper, which was the base for - still written on paper - statistics on

number of deliveries and others.

This

form was sent to the county where three people did the input in the DHIS2-system,

the national medical / administrative database as a kind of datawarehouse that

was aimed to guide health care policy on the county level and the national

level. Now structured data were gathered on cancer so that screening or early

diagnoses mostly depended on the knowledge and attention of the care provider.

Dr.

Kenta was not aware of any training for cancer prevention screening, diagnosis

of treatment within the last year.

Nevertheless,

she pointed out that it was necessary.

Slightly

opposing her quite passive attitude, I wondered who was responsible to take

initiative to organize certain educations.

Mostly

they seemed to be set up and funded by third parties (from abroad) and had to

be approved by the county and the Central Ministry.

So

there were three “owners” in the triangle who could take initiative …

In

our exploration to have an idea of the relevant size of public, private not for

profit (confessional) and private for profit health care provision, we got

quite substantial different figures regarding the source.

She

spoke about fifty public facilities in a total of three hundred.

Only

some private centres received money from the government as for example “Hope

for Women.”

Her

slightly submissive, uncertain attitude towards our inquisitory asking turned

triumphantly in a confident clinical authority when I had to beg her for the

toilet because of diarrhoea and she provided me with Flagyl to kill the

beasts.

We

visited a health centre where a team of five nurses and physician assistants

provided consultations

without the supervision of a doctor.

He

had had his education as a gynaecologist

obstetrician in

in the United States

and had worked there for many years.

He

corrected my conviction that chemotherapy was

not administered

in JFK (I

thought only planned for the gynaecology

tumours in September)

as he referred for example to chemo for Burkitt lymfoma with children.

I

was surprised

that children

oncology, which

was a high specialized

service in some University Hospitals

in Belgium, seemed to be a common practice in this hospital.

Mr.

Slewi, member of

the NCD unit and responsible for

the cancer registry, explained that

they were preparing since

2012.

They

had collected

data on a monthly basis

from six facilities since

May of this year. The most important source

of registration

was the pathologist’s diagnosis

within the JFK hospital.

They

also gathered

cancer reporting

from other centres without

pathological confirmation,

but they tried to convince the treating doctor

to refer these patients for

a pathological confirmation

in the JFK.

I

was also difficult to eliminate doubles:

patients who were seeking for different advices

in different centres.

By

the lack of a national identification

number, they asked names, birthdates, addresses and telephone numbers but as mentioned these data were not reliable.

Johnson

emphasized on

education and

awareness of

cancer issues:

“illiteracy

is the biggest problem in

this country “

At

that moment

data were collected by a standardized

registration form,

Slewi showed me,

that was filled in by a doctor or mainly by the pathologist.

He

showed us his small desk and dusty computer

donated by the WHO, where he was putting the data into an excel file, so he could make some statistic overviews.

A

special input software

from the African Cancer

Registry Organization

would soon be available but there was no link with the government

database DHIS2.

Nicholas

De Borman, head

of the Belgian software

consultancy company

Bluesquare,

who had already done

some work for the PBF unit of Vera Mussah, emphasized

that all applications and

apps developed

for low and middle intercom countries should

better be integrated

within the DHIS2 system.

During

a late lunch in a fancy African restaurant, Vera noticed me that it was forbidden to take pictures of people without

their permission.

She

didn't notice

that I was seduced by the African colours of the paintings

on the wall more than the people in the restaurant.

Not

respecting the

time schedule

because of my unsatisfiable

curiosity, we missed the appointment with

the WHO lady and - I presume the dean of the faculty of medicine had left the spot where we would have met him:

At

the Ministry, we had a last reunion to prepare the mission of August.

Embraced

by the NCD-team that did a lot of effort to make the mission happen.

Glad

being part of this dream team…

Back in the hotel I requested the receptionist

to provide me with a confirmation of my room reservation in August.

She did not succeed - due to the failure of the

Internet - and despite five reminders from my side, to make a confirmation

until just before I left the next day at twelve o'clock, although on paper,

because she could not send an email because of the internet that was being shut

down.

I did not know whether I should be angry or

have pity.

As a perfect host, Vera escorted me to the

airport or was there for another half an hour with me to taste the luxury of

the Farmington Hotel built by the Chinese.

I posed for her in the garden and at the river

and rewarded her with a lunch and a delicious glass of white wine.

Finally, she had fulfilled a Celestine promise

for me.

With thanks to :

-the NCD team for preparation and guidance of the visit

-Lonely Planet West Africa

-Lut Brugmans voor de omzetting van klank naar tekst

-Lonely Planet West Africa

-Lut Brugmans voor de omzetting van klank naar tekst